“Life of a So-Called Texas PreacHer” is an experimental novel of personal narrative, oral family histories, poetry, and auto-fiction. Beginning in a fertility clinic in Los Angeles and weaving between experiences of moving home to Houston and “back home” to Grapeland, Texas, the novel focuses on the infinite iterations of Kamaria. Kamaria is also the first name of the author. A ride through unclear time descriptions, blurry landscapes, misunderstandings and questions of consent and belonging the reader is lost in memory and thought. Just like Kamaria we are all the while wondering which Kamaria is moving us through the story. Are we ourselves and how do we know we are truly ourselves even when we are constantly re-evaluating/re-developing ourselves? What is the core of a person? Can we start anew? A virgin even? Does when we are born matter and do we really control when we can and will have a baby? And with whom? Kamaria asks if time traveling within not only one’s own family history but within one’s own personal history will allow us to escape with an understanding of reality. Can we leave with an understanding of reality that doesn’t seem ready for Black bodies, Black intellectual impact, and Black wealth in ways that benefit Black people? Are African Americans a community of starving artists exploited, and jump scared at every turn? Kamaria goes “back home” through time travel, tradition, and culture in a multifaceted attempt to somehow not lose all of herself. This novel as well as Shepherd's paintings, drawings, and prints, and family photographs give space to mediate within the space of being a Black woman in and out of the United States. These different forms of Kamarias whether in text or image are self-portraits. These self-portraits are copies and reincarnations. Through language and mark making Shepherd forms her own language of understanding identity. Kamaria is re-exploring historical and Black experience through time. The Kamarias are a timeline. The Kamarias are a documentation of selves or selfies from one day or year or generation to the next. How is Kamaria experiencing what her grandmother experienced and what is different between their experiences? What is the difference between experiences that are unique to them as people and experiences that are unique to their time? Will we all be Kamarias by the next century?"

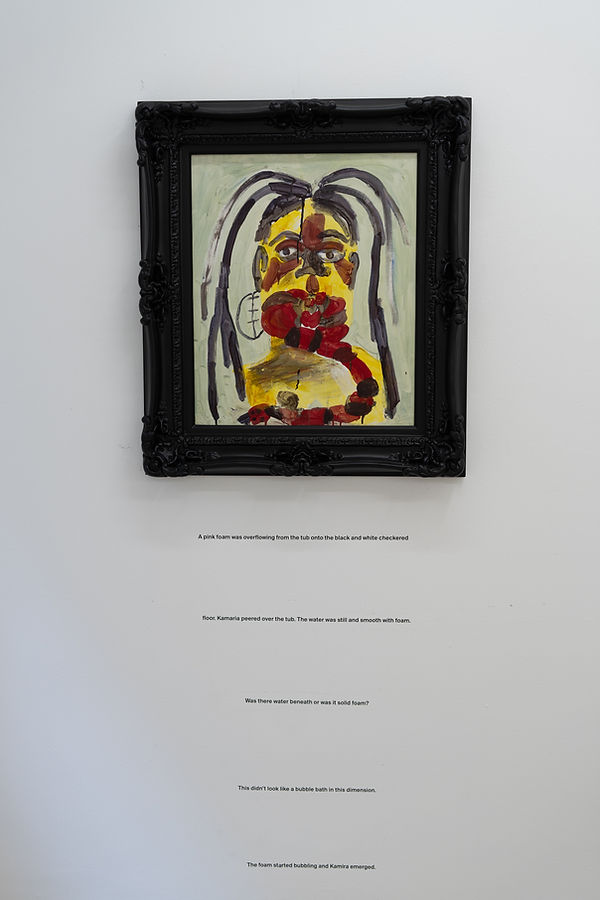

Kamari's painting of Kamria (present-day), 32 x 28 framed, egg tempera on masonite, 2025

The vinyl text beneath the painting reads:

"A pink foam was overflowing from the tub onto the black and white checkered floor. Kamaria peered over the tub. The water was still and smooth with foam. Was there water beneath or was it solid foam? This didn’t look like a bubble bath in this dimension. The foam started bubbling and Kamira emerged."

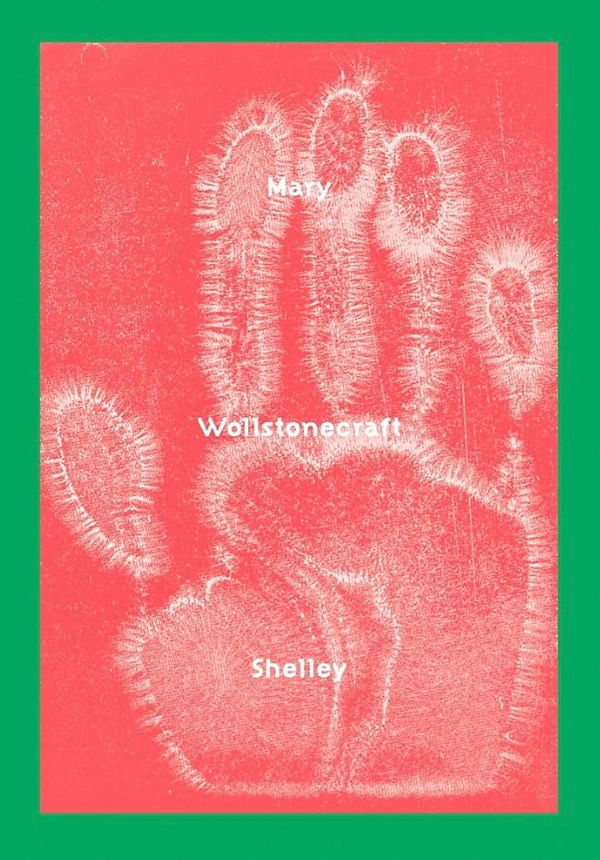

"Foretelling a cataclysmic global pandemic and economic and climate collapse, Shelley's dystopian vision of the 21st century is re-envisioned by contemporary artists and writers

Conceived and edited by Meg Onli, the Nancy and Fred Poses Curator at the Whitney Museum of Art, The Last Man is a radical reissue of Mary Shelley's apocalyptic 1826 novel on the eve of its 200th anniversary. A dystopian tale of emotional, social, political and planetary devastation set in the 21st century, Shelley's text is reframed through the visual and textual commentary by artists and writers from the Image Text MFA program at Cornell University. Shelley's profoundly relevant reflections on the corruption and vanity of power, and our blindness to the terrible transience of human desire and ambition, are here amplified, annotated and translated into fragments of our troubled present by the artists' contemporary interventions."

Artists include: Maddy Bremner, Nelis Franken, Catherine Gans, Danielle Garcia Tubo, Maxwell Harvey-Sampson, Sara Minsky, Marié Nobematsu-Le Gassic, Monica Regan, David Richards, Crystal Lamar, Genevieve Sachs, Yonatan Schechner, Kamaria Shepherd, Christopher Stiegler.